Will Oil’s Decline Crush Energy PE Funds

by Michael Roth

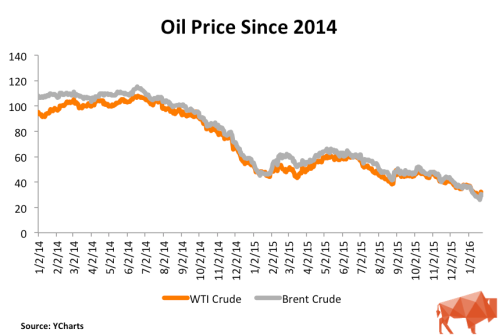

The conventional wisdom is that energy fund returns and oil price movements go hand-in-hand. Since the beginning of 2014, oil prices have fallen 70% and they have tumbled 50% from where they were just since the end of Q2 2015. Does this mean that energy funds are destined for a similar decline?

Our Q3 2015 performance information is still coming in and Q4 data is a few months away. Therefore, I turned to our fund and cash flow data to determine whether or not the 50% fall in oil prices will mean energy-focused funds should expect a similar drop-off. Using regression analysis, I compared the quarterly energy fund returns to both the quarterly returns of WTI crude and the broader Energy Price Index maintained by the World Bank.

Is There A Link Between Energy Funds and Oil Prices?

WTI Crude Analysis

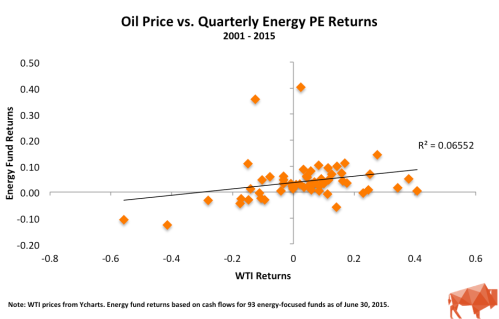

I used our Bison funds to analyze the cash flows of 93 energy-focused private equity funds with vintage years between 2001 through 2013. These funds represent a little more than $160 billion of committed capital to the sector during this time. I grouped the funds into a portfolio and ran a simple regression analysis of the quarterly time-weighted returns against the quarterly returns of WTI crude oil.

The scatter plot appears to show some correlation between oil prices and energy fund returns but the relationship (R-squared) is weak. R-squared values below 0.5 are generally not considered strong and a value of 0 indicates no relationship. Part of the reason for the low R-squared are the two noticeable outliers. These are from Q4 2004 and Q2 2005 and both instances can be attributed to large valuation increases in First Reserve IX and Carlyle/Riverstone Global Energy and Power Fund II. If you excluded these quarters from the analysis, the R-squared jumps to 0.296 – a 4x increase but still well below a value that is considered meaningful.

Energy Price Index Analysis

The Energy Price Index is a weighted average of global energy prices maintained by the World Bank. Specifically, the index is weighted as follows: Oil – 84.6%, Natural Gas – 10.8%, and Coal – 4.7%. During the second half of 2015, this index experienced a decline similar to WTI oil prices, falling 37%. I used this broader measure to see whether a more comprehensive index may show a stronger correlation with energy fund returns.

Similar to the comparison against the WTI oil price, the scatter plot appears to show a correlation but the R-squared of 0.092 indicates that the relationship is not strong.

Why Is the Correlation Weak?

There are likely a number of reasons why energy fund returns may not be entirely correlated to oil prices. Major variables include:

- Initial purchase price

- Debt levels

- The presence of hedging contracts

- Diversity of business’s operations

- Portfolio diversification over several years

- Insufficient sample size (n = 56, which covers 14 years of quarterly data)

The first four considerations could indicate why a company could performs independent of oil prices. Portfolio diversification would be the GP’s attempt to invest in companies over several years which should mean they are investing in companies at different points in the energy price cycle. Another possibility is that the sample size is not large enough to be meaningful. A sample size greater than 100 is generally considered meaningful.

If oil prices aren’t the answer, could the reality be that energy fund returns are related more to their buyout fund brethren than to oil? Going back to our Bison funds, I ran a simple regression analysis of quarterly energy fund returns against a portfolio of 402 North American and Global buyout funds, excluding energy funds, from 2000 – 2013.

As the chart above shows, the R-squared of 0.433 is much higher than 0.066 – the R-squared of oil and energy funds’ returns. This R-squared is still below the meaningfulness threshold of 0.5 but this could indicate that energy private equity fund returns have a closer relationship to buyout funds than they do to energy prices.

Wrapping Up

Make no mistake, the steep decline in energy prices will negatively impact energy fund returns in Q3 and Q4 2015. However, the analysis above highlights that the price of energy is not the only factor, and may not even be the primary factor, that contributes to the energy fund returns.