Digging In To Distributions: An Update on Venture Capital’s Issue

by Michael Roth

Last summer, I highlighted the glaring lack of distributions within the VC industry since the late 1990s. It’s been over six months since I published that piece so I wanted to provide an update on where things stand through June 30, 2015.

VC Funds Have Cashed Out Where They Could

Venture capital funds saw a strong distribution pace during the first half of 2015. Looking at the DPI:TVPI ratios, the 2003 – 2007 vintage years saw a noticeable increase – improving by 32% on average. Three of those vintage years jumped above 0.5 barrier which means the average fund has distributed more than half of its total value. As a reminder, the DPI:TVPI ratio is a measure of how much of a fund has been realized (a ratio of 1 means the fund is fully realized).

DPI Multiples Improved but Still Below 1.0x

DPI multiples are still struggling to reach 1.0x, which means the average fund since 1998 has yet to return 100% of what investors have paid in.

The two years that stick out are 2003 and 2010. These are the vintage years that saw the biggest increase in median DPI. 2003 sticks out because it is on the cusp of a 1.0x DPI multiple but 2010 actually saw a bigger increase, percentage-wise. Funds that drove the increase in 2010 include Union Square Ventures Opportunity Fund and Insight Venture Partners VII on the tech side and Third Rock Ventures II, Orbimed Private Investments IV, and MPM Bioventures V on the healthcare side.

VC DPIs Lagging But TVPIs Not As Far Behind

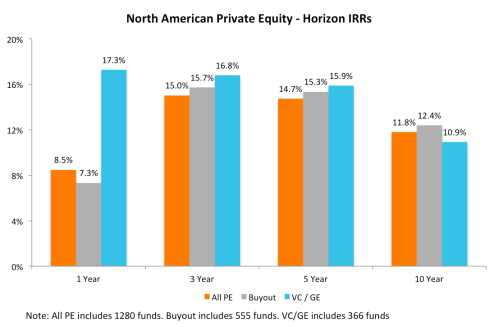

My analysis of VC distributions so far has highlighted the positive developments. What can’t be ignored is that these positive developments have not occurred in a vacuum. The buyout industry’s DPI multiples also improved and are still higher than the venture capital industry for 13 of the 15 vintage years from 1998 through 2012.

While the DPI multiples have clearly been lagging, venture capital’s median TVPI multiples have shown strength over recent vintage years. The big question is whether these TVPI multiples are real or is it a matter of time before they come back to reality.

Final Thoughts

Venture Capital had a solid two quarters to start off 2015 but the DPI issue still remains. Since the industry is prone to large valuation fluctuations, the ability to cash out when times are good is an important part of being successful. This analysis is also important because investors need to analyze and decide whether an allocation to venture capital is worth the risk.

While DPI multiples have increased across nearly every vintage year, the DPI:TVPI ratio is still lower than that of the buyout industry for all but one vintage year since 2000. This means LPs remain highly exposed if this current cooling off phase accelerates into a bigger decline.