The media has made a big deal recently about private equity fees due to the revelations that CalPERS and CalSTRS have not kept track of the fees paid and carried interest earned by their private equity managers. More broadly, there is an increasing effort by LPs to receive greater disclosure about fees and reduce expenses.

My concern is that, in most cases, the focus on fees overlooks the real question: Do private equity returns justify the amount paid in fees and carry?

In this post, I will analyze the management fees paid to private equity managers but also look at them in the context of returns generated. Good returns should be rewarded but perhaps the conditions for receiving carried interest should be revisited.

Public Equity and Private Equity Fees Are Structured Differently

Private equity fees are frequently criticized as being outrageous in relation to their public market mutual fund peers. The glaring problem with this comparison is that mutual funds and private equity funds charge their fees on a different base. Private equity funds charge a 1.5 – 2% fee on commitments during the 5 year investment period. Thereafter, funds typically charge .75 – 1.25% of net asset value. Mutual funds charge an ad valorem fee, meaning the fee is charged on the fund’s NAV. As the fund’s value increases, your management fee, in absolute terms, goes up.

To get a sense for the cost of management fees, I chose to compare Carlyle Partners IV to an index fund, a large cap mutual fund, and a small cap mutual fund. These three mutual funds will highlight the impact of fees at the different fee levels.

Clearly, an index fund charges a fraction of the cost of a mutual fund or a private equity fund. However, if you have an investment mandate to earn returns in excess of the market, you are not going to choose an index fund. The more interesting comparisons are the large cap and small cap mutual funds against Carlyle IV. Just glancing at the numbers, it appears that Carlyle Partners IV is charging more than twice as much as Fidelity and 21% more than Putnam’s fund.

Fees Need to be Viewed on an “Apples to Apples” Basis

Critics inaccurately condemn private equity because they just look at the headline number. Let’s compare the cost of fees over a 10 year period to evaluate the true cost over the typical private equity fund’s life. For the three mutual funds, I used their 10 year returns in my assumptions to calculate the average fee over time.

For Carlyle IV, I assume the fees are the same as what they are for their more recent flagship funds. I use the fund’s actual NAVs, based on Bison’s cash flow data, to determine the post-investment period fees.

Over the 10-year span, Carlyle IV’s fees were just 6% more than Fidelity’s fund but were 40% LESS than Putnam’s fund. When an accurate comparison is done, private equity management fees do not look nearly as egregious as headlines may lead you to believe.

You Must Consider Returns

The question I asked at the beginning was whether or not private equity returns justify the amount paid in fees and carry?

To answer this question I looked at returns in two ways. First, I performed a simple analysis which calculated a TVPI multiple for the public market funds using their 10-year average annual return.

Using the 10-year CAGR for the three mutual funds, I arrived at each investment’s value after ten years. The TVPI multiple is equal to End Value / Commitment. Despite an average management fee that was 6% higher AND a 20% incentive fee, Carlyle IV managed to generate 13.6% more value than Fidelity’s fund. In the case of Putnam’s fund, Carlyle IV outperformed the fund while costing almost $700,000 less than in management fees.

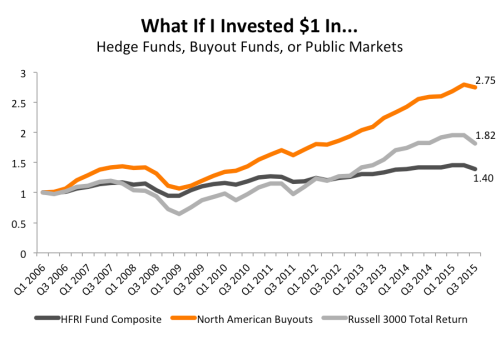

This comparison is not completely relevant for analyzing a private equity manager because it ignores the PE manager’s ability to manage the cash flows. To account for this, I performed a PME analysis against the S&P 500 Total Return Index. The analysis tells a compelling story about the differential between Carlyle IV and the public markets.

Buying and selling the S&P 500 Total Return Index at the same times as Carlyle IV would have resulted in a 1.22x TVPI multiple and a 3.65% net IRR.

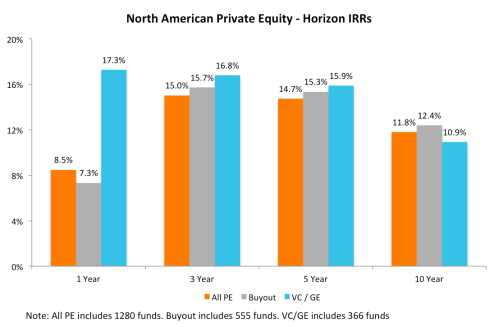

For those who think I may have selected a very convenient example to illustrate my point, I would refer you to my last piece, which analyzed the PME performance of North American and Global private equity funds. In nine of thirteen vintage years, buyout funds outperformed the Russell 2000. Digging into a fund level analysis, 52% of buyout funds analyzed outperformed the Russell 2000.

Carried Interest Hurdles Rates Should be Changed

When a fund’s returns are good, their fees look justified but what can you do when the returns are poor? Private equity gets it right by structuring the fees to have an incentive component. It is hard to justify Putnam earning 1.7% on average over the last 10 years given that they have returned just 6.2% annually.

Despite the conditional nature of carried interest, there is still an outcry over their payment. Part of this is partisan political beliefs that will never be satisfied but part of it is due to insufficient hurdle rates. There is a mismatch between the return expectations LPs place on themselves and the GPs. Internally, many LPs expect private equity to beat the public markets by 200 – 300 bps but they allow GPs to earn carried interest by generating an IRR greater than 8%. LPs should force GPs to meet the same return hurdles that they place on themselves.

Wrapping Up

Private equity fees are appropriately divided into management fees and carried interest. This ensures that managers are incentivized to maximize returns and not just accumulate assets. To ensure that incentives are completely aligned, the hurdle rate should be modified to acknowledge the link between public markets and private equity markets. Strong performance should be rewarded but that reward should include a condition that the manager generates excess returns over a market benchmark.